Understanding the differences between a decree, an order, and a judgment is essential for students studying civil procedure. These terms have distinct meanings and roles under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC). Below is a detailed explanation of each concept, followed by a comparative analysis.

1. Decree

Legal Basis: Section 2(2) of the CPC

Definition:

A decree is the formal expression of an adjudication that conclusively determines the rights of the parties concerning all or any of the matters in controversy in a suit.

Key Characteristics:

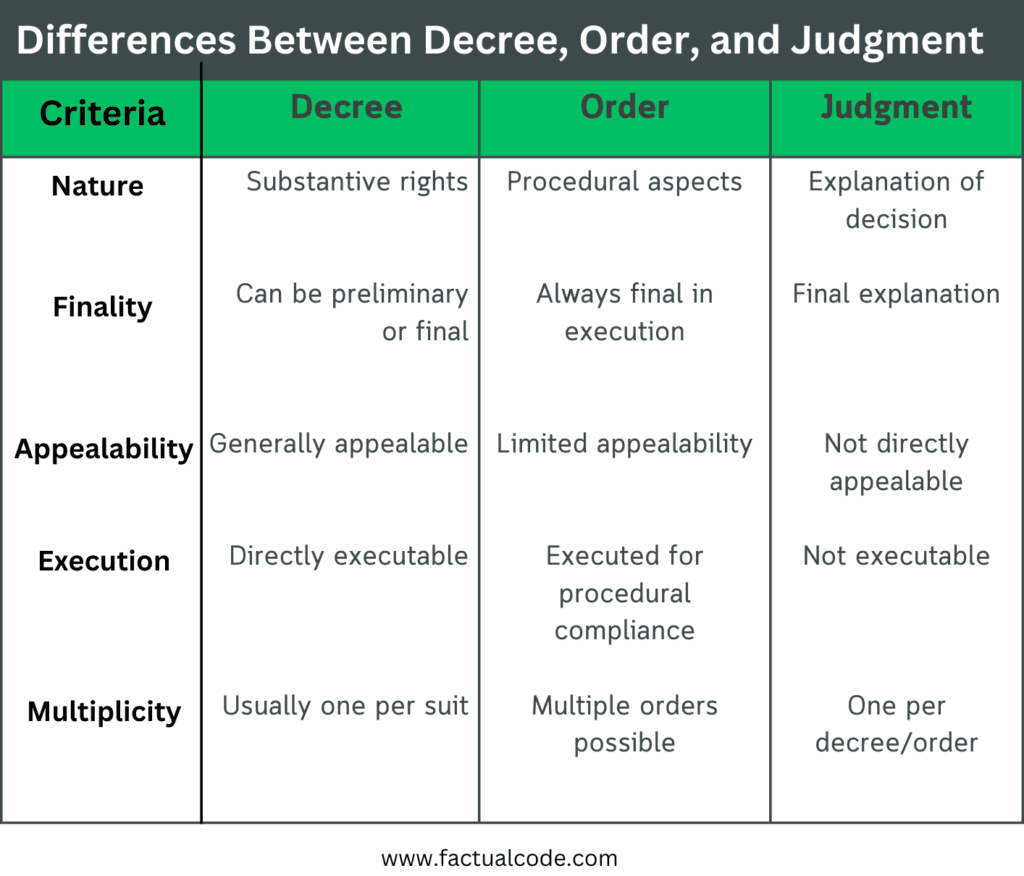

Substantive Rights: A decree determines substantive rights of the parties involved.

Types: Decrees can be Preliminary, Final, or Partly Preliminary and Partly Final.

Finality: Decrees have a decisive nature unless they are preliminary.

Appealability: Generally appealable under Section 96 of CPC, unless prohibited.

Example:

A court deciding ownership in a property dispute case issues a final decree.

2. Order

Legal Basis: Section 2(14) of the CPC

Definition:

An order is the formal expression of any decision of a civil court which is not a decree.

Key Characteristics:

Procedural Rights: Deals with procedural aspects rather than substantive rights.

Nature: Always final concerning its execution but may be interlocutory.

Multiplicity: Multiple orders can be passed during the course of a suit.

Appealability: Limited appealability as per Section 104 and Order 43 Rule 1.

Example:

An interim order granting a temporary injunction to prevent harm until the final decree is passed.

3. Judgment

Legal Basis: Section 2(9) of the CPC

Definition:

A judgment is the statement given by the judge on the grounds of a decree or order.

Key Characteristics:

Detailed Explanation: Provides reasoning, legal principles, and analysis supporting the decision.

Formality: Must be written and signed by the judge.

Basis for Decree/Order: Forms the foundation for issuing a decree or order.

Non-executable: A judgment itself is not executable.

Example:

A detailed written judgment explaining the reasons for awarding damages to the plaintiff.

Differences Between Decree, Order, and Judgment

Suit of Civil Nature

Definition and Concept:

A “Suit of Civil Nature” refers to any legal proceeding involving the assertion of civil rights and obligations rather than criminal liability. These suits seek relief in the form of compensation, injunction, or declaratory judgment rather than punishment.

Legal Basis: Section 9 of the CPC

This provision empowers civil courts to try all suits of a civil nature except those explicitly or impliedly barred.

Key Elements of a Suit of Civil Nature:

Subject Matter: The dispute must involve civil rights or obligations, such as property ownership, contractual obligations, family disputes, or commercial matters.

Relief Sought: Remedies such as monetary compensation, injunction, or declaratory judgments are typical in civil suits.

Parties Involved: Civil suits generally involve private parties (individuals or entities) rather than the state.

Illustrations:

Case Study: Property Dispute

Example: Person A sells a piece of land to Person B. Later, Person C claims that the land belongs to him and that Person A had no right to sell it. Person C files a suit against both Person A and Person B seeking a declaration that the sale is void and requests restoration of possession of the land.

Nature of the Dispute: Property rights, hence a suit of civil nature.

Relief Sought: Declaratory judgment and restitution of property.

Jurisdiction: Civil court has jurisdiction to adjudicate as it pertains to a civil right.

Family Dispute:

A suit seeking custody of a minor child between estranged parents qualifies as a suit of civil nature.

Exclusion from Civil Nature:

Certain disputes are excluded from being categorized as suits of civil nature, such as:

Public Rights: Disputes concerning public rights (e.g., election petitions) are generally excluded.

Matrimonial Offenses: While civil family disputes are included, criminal offenses like dowry harassment are excluded.

Religious Matters: Purely religious or caste issues are excluded unless they involve civil rights.

Judicial Interpretation:

Indian courts have interpreted the term broadly to include disputes that indirectly involve civil rights.

Case Law:

Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams v. Thallappaka Ananthacharyulu (2003)

The Supreme Court held that even disputes involving religious offices are of civil nature if they pertain to civil rights.

Conclusion:

A decree, an order, and a judgment play distinct and crucial roles in the judicial system. While a decree determines substantive rights and is executable, an order focuses on procedural matters, and a judgment provides the reasoning for the court’s decision. Additionally, a suit of civil nature forms the backbone of civil litigation, encompassing a wide range of disputes involving civil rights and obligations. Understanding these distinctions is fundamental for law students and practitioners alike.